By Shu’aibu Usman Leman

The horrific scourge of armed banditry across North-West Nigeria has plunged the region into one of the darkest and most tragic chapters in our nation’s recent history. From the epicentre in Zamfara, the violence has spread across Kaduna, Sokoto, Katsina, Jigawa, and Kebbi, bleeding into parts of Niger State.

The entire geopolitical zone has been relentlessly battered by waves of deadly attacks, mass abductions, livestock rustling, and the deliberate destruction of entire communities and farm The resulting humanitarian and economic toll is staggering, demanding nothing less than urgent and decisive action from both Abuja and the affected state governments.

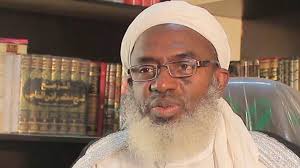

It is within this deeply troubling context that Sheikh Ahmad Abubakar Gumi, a prominent Kaduna-based Islamic cleric and former military officer, has controversially waded into the crisis with a proposition that, though fiercely debated, remains thought-provoking. His direct engagement with various bandit groups, offering spiritual guidance and advocating dialogue and amnesty, has sparked a highly polarised national debate.

Gumi’s efforts seek to address the entrenched grievances believed to be fueling the conflict.

While many, myself included, disagree with some of Sheikh Gumi’s political pronouncements and methods, the underlying security argument he advances deserves honest, measured reflection. We must resist the urge for emotional dismissal and instead rationally examine any ideas—however unconventional—that could contribute to sustainable peace in the region. To reject potential solutions outright would be a costly mistake.

The cleric’s initiative involves personal interaction with Fulani herders and armed groups who have inflicted immense suffering on the region’s people.

In his meetings, he preaches about the sanctity of human life in Islam, urges the fighters to abandon violence, and has even invested personal resources in building schools to educate pastoralist youths.

These efforts highlight a genuine attempt at long-term reorientation and rehabilitation.

Sheikh Gumi argues that many of these young men have lost their moral compass largely due to a lifetime devoid of education, guidance, and spiritual grounding.

He insists that without meaningful reintegration through education, moral instruction, and socio-economic inclusion, military force alone cannot end the crisis. He calls for a holistic approach that blends force with reform.

To some observers, Gumi’s interventions appear noble and humanitarian; to others, dangerously naïve and potentially legitimising criminality. Yet, his involvement exposes an inconvenient truth: for decades, the North-West has suffered chronic governance failure. Vast areas have been left without state presence—no schools, hospitals, motorable roads, clean water, or adequate security infrastructure.

In these abandoned spaces, resentment and lawlessness inevitably take root. Criminality thrives in the vacuum left by governance collapse. This painful reality underlies the current security nightmare in Zamfara, parts of Kaduna, and the hinterlands of Katsina, Sokoto, and Niger states.

However, recognising these root causes must never excuse the atrocities committed by the bandits. No grievance can justify the slaughter of innocent citizens, the burning of farms, the kidnapping of schoolchildren, or the violation of women.

These are crimes against humanity, and the perpetrators must face justice.

Therefore, dialogue must never replace enforcement. A sovereign state that surrenders its coercive authority becomes a playground for violent non-state actors. Engagement may play a role in certain stages of conflict resolution, but it must never be mistaken for weakness.

For any negotiation to be meaningful and sustainable, the Nigerian State must first demonstrate overwhelming force.

The armed groups terrorising the North-West must be degraded militarily and psychologically.

They must be made to understand that the State is stronger, better organised, and fully capable of neutralising their threat. Only when these criminals are weakened, fragmented, and cornered should dialogue become an option—and it must be pursued from a position of strength, not desperation.

The military campaign must, therefore, be intensified and sustained—not relaxed prematurely. Intelligence-led operations, precise aerial strikes, coordinated ground offensives, and the use of advanced surveillance technology must continue. Security personnel must be properly equipped, motivated, and supported to endure the rigours of prolonged counter-banditry operations.

Yet, even the most effective security operations cannot deliver lasting peace on their own. The North-West simultaneously suffers from dire educational deficits, poor healthcare, massive youth unemployment, and pervasive poverty. In many local government areas, schools and primary health centres simply do not exist. This socio-economic vacuum fuels radicalisation and recruitment into armed groups.

Once stability begins to return, the government must immediately launch a comprehensive rebuilding and rehabilitation programme—providing quality schools, functional clinics, grazing reserves, clean water, mobile police units, and accountable local administrations. This broad development drive must rebuild trust and form the foundation of a new social contract between the State and its long-neglected communities.

In this respect, Sheikh Gumi’s emphasis on education and moral reorientation holds real value—if implemented within a strong, government-led security and development framework. Such efforts must not be left to individuals acting alone; they must be professionally structured, transparent, and accountable to prevent abuse or perceptions of bias.

The reintegration of repentant fighters, if ever considered, must be handled with utmost caution. Only those who demonstrate genuine remorse and surrender their weapons should qualify for rehabilitation. The rights and emotions of victims must not be ignored in the pursuit of peace. Reconciliation must not mean forgetting.

Above all, the government must avoid sending the dangerous message that violence is a shortcut to state attention or reward. Lessons from past amnesty programmes show that compensating criminals can encourage more violence rather than end it.

The correct sequence for achieving lasting peace must therefore be clear: first, the government must secure and dominate the territory; second, it must establish governance and infrastructure—schools, clinics, local administrations; and only then, from a position of control, should dialogue be considered.

Sheikh Gumi’s voice is one among many. He does not hold the complete solution, but his willingness to challenge the status quo has forced an important national conversation. The path to security in the North-West requires more than bullets—it demands a blend of decisive force, robust development, community engagement, and moral renewal.

Ultimately, the responsibility lies with the government—not with individual clerics—to design, fund, and implement a coherent, comprehensive security and development strategy. The security and welfare of the North-West cannot be outsourced to private initiatives. The Nigerian State must reassert its authority with conviction, capability, and transparency.

If the government can effectively balance sustained military strength with inclusive development—investing in education, healthcare, and trust-building—then true and lasting peace, rooted in justice and opportunity, can finally emerge across the North-West.

The resilient people of this long-suffering region have endured unimaginable pain. They now deserve lasting security anchored in wisdom, courage, and an unwavering commitment to national sovereignty and the rule of law.

Leman is a former National Secretary of the Nigeria Union of Journalists (NUJ).